Those who excel at anything in their lives have a way of making that effort, that interest, that passion become all pervasive and yet not all consuming in their lives. It’s simply in their nature to always be thinking about that passion, somewhere, some way, some how in the their subconscious when they are doing just about anything else.

What’s the simple evidence we see every day? Any devoted athlete, awesome chef, charismatic leader, ambitious scientists or all star parent will consistently be ready at any time to engage anyone in a deep, thoughtful conversation about that passion. Then what’s the burning question? How can an organization become like that? How can we ourselves create the circumstances, the overall attitudes and approaches and then results that allow us to do the same as best we can – without huge investments in programs, processes, consultants that never seem to really deliver the results we all believe possible.

For us it’s all about the Adaptive Innovation lifestyle and it’s the basics, however simple they are, that set the stage for employing its principles in our own ways. No rigid programs, no extensive training, no bare feet and yes, there are bad ideas that really need to die as they germinate.

So, here’s an update on our initial post, but with a few added observations:

Adaptive Innovation: An Introduction

Adam Malofsky, Ph.D.

Steven Levin

Innovation. It’s an often used, likely over used word these days, from describing a new juicy hamburger to a suspension system on a new car to the title of the one now responsible for either the company’s future or at least the representation to analysts that innovation is important to our company. There are all kinds of innovation it seems, from the historically noted closed big firm type to today’s open innovation initiatives, with even entire firms dedicated to open innovation’s natural gravitation towards a transactional exchanges of ideas, discoveries and capabilities. The bottom line is that we are all in search of how to efficiently, effectively and consistently advance our firm’s, institution’s or individual efforts towards achieving wide ranging goals on an on going basis. Most would agree that to do this in a world where accessible information is accumulating on ever accelerating rate at an ever escalating scale, we need to manage our ability to develop new approaches and ideas much more effectively, at least at a rate exceeding that of our competition. In other words, we need to innovate efficiently, effectively and consistently to create value in the same way. What we have seen is that most efforts to date seem to be, while effective, still piece meal and not comprehensive in nature to many types of situations. In our view, we believe that a holistic, consumer derived, multi-disciplinary approach that we call Adaptive Innovation may be the key to survival in our ever-changing world.

Specifically, we have spent the last ten years distilling our own and a lifetime of others experiences into a an approach towards innovation that takes into account the latter requirements without taking on a single codified process that in and of itself, becomes self limiting by definition. In fact, the last few years have even seen now startups created with this new approach, including Sirrus, formerly Bioformix, one of the largest materials and energy saving opportunities ever created.

What did we do? ,We looked to historical context to reveal an approach, versus a process, that is holistic in nature and that can accordingly be applied to vast number of highly varied situations. In the end, we have noticed that the most effective innovators use the common approach of adapting themselves and thus their efforts and processes to their world’s environment. They do not simply use closed or open innovation. They use both and maybe ten other hybrid or alternate approaches at the moments in time they are appropriate. In using an adaptive approach to how they interact with their world, many different processes and tools allow the adaptive innovator be able to rapidly uniquely accumulate vast amounts of customer and technological information to develop insights within a consumer context that allows a transformation of that information into customer context and knowledge where regularly and consistently emerging innovative ideas are reduced to practical, inventive practice for commercial use.

We also noticed that per Arie DeGues (The Living Company, 1997), formerly of Shell, that those who were generally conservative and yet highly in touch with the world around them, whether consciously or in the background, created a long lasting culture of holistic thought. This culture encouraged a world where ideas could be developed over lifetimes or even beyond with the accumulated thoughts of single and many people so well communicated that when the moment arrived within the well communicated context of simple, clear stories of the future, the innovation happened quickly, capably with little risk and well ahead of the competition.

We call this holistic approach Adaptive Innovation, where consumer understanding allows for the contextual development of insights and consumer experiences that can be translated into innovation (ideas that can create value) and invention (reduced to practical, commercial applications). While the ways people and groups work vary widely, as studied by Peter Senge and others, five groups of work emerge, three of which are of true interest to most practical innovators today. Those of key interest to innovators are in bold:

General Needs Understanding

– What makes people happy and satisfied? In other words, what is of value?

Discoveries

– What fundamentally defines our world? This refers to the fundamental sciences.

Insight

– Conceptually, what specific features make people happy and satisfied?

Innovation

– What single or collections of features can be assembled?

– How can they create realizable value?

Invention

– What must be true for an innovative idea to work, to actually deliver value?

– What specific inventions, new or already existing, are required?

– The actual development of practical products that reflect the innovative idea

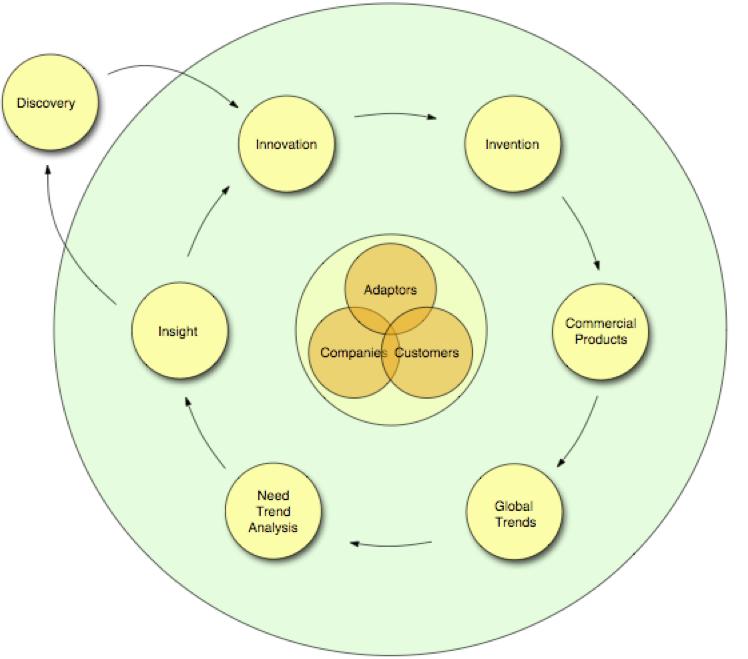

We see a flow of events related to the above that do seem sequential, like a linear process, but that are likely only generally that way. This is illustrated below.

Figure 1 : Simple Work Sequence for Product Development

While any number of loopbacks and interrelationships are plausible and in fact reasonable, our illustrations purpose for understanding Adaptive Innovation is that a constant feedback loop exists where to effectively innovate and invent, a much more significant process of observation, analysis and insight are required. These observations can come form current commercial activities and products as well as an in depth knowledge of global social-demographic trends. As information is accumulated and processed, a constant analysis must to be done to ascertain a cascading priority of needs to develop insight into what is of realizable value versus something that is relatively unimportant to a particular group. Basically, all innovation must start with and essentially be initiated by the consumer, the user.

Insights then generally feed and direct two basic sets of activities grounded in the areas of discoveries in fundamental science that by their nature, are of long term research to practical application or, alternatively, in the area of innovating, that is, developing practical ideas for specific products or features of interest to consumers today. Discovery, by its nature, are activities not generally germane to today’s commercial activities, but are critical to tomorrow’s activities. Accordingly, we separate these activities and see them as carried out primarily by government institutions, think tanks, universities and other collaborative efforts supported by industry and the public at large for the long term benefit of product and service innovation.

An innovator’s job is to deliver ideas that can make money, that is, ideas that can realize real value if a product reflecting the idea is developed. The innovator must develop a solid, commercially grounded story of why and how the idea will work at delivering value, not simply state an idea. The idea is not likely even a product, but rather it is likely a feature. A collection of features is reflected as a product that delivers a probably single, overt benefit. A business model must be developed at inception or the idea is simply of no practical value. The innovator is essentially responsible for developing a good commercial story about an idea that reveals, without even a prototype necessarily, the what must be trues for the idea to succeed. These what must be trues are essentially feature and/or product specifications that then guide the invention activities. The objective is to reveal those ideas that have a good story where their likely inventive realization is based upon existing commercial features versus requiring fundamental scientific discoveries.

The invention activities center upon translating the innovative idea and it’s specifications to practical, commercial reality as a product feature. What inventions are already commercially available and have an existing supply chain? From which industries may they be derived? What features will require an actual invention? Can the inventive requirement be reduced into basic enough elements to reveal existing, practical inventions that on combination solve the need? Is a longer inventive process required? Is a basic scientific discovery required to allow the idea to become a reality? Finally, once assembled, do we have a product that meets all the requirements, including the commercial one of creating value?

While seemingly simple, putting all of these activities together can be complex and difficult to manage. The more inventions required, especially when from multiple disciplines, the more and more complex the management. The more different from conventional approaches, the more complex the development of a simple, positive consumer experience. In any case, these activities can be conducted in any number of ways with many different tools and processes. The contention of adaptive innovation is that many different approaches are plausible and that the best innovators will simply be those who can best manage the vast tool set and simultaneously be able to effectively know when to use what when and how. In fact, it is our view that the number and types of processes and tools are so vast and the situations that emerge are so varied, that no single company can likely reinvent itself to handle them all alone. Adaptive innovation accordingly reflects this by acknowledging that rather than have companies expend vast resources trying to reinvent themselves, companies should instead seek to reallocate resources in such a way as to allow for their adaptive interaction with many different resources, capabilities, processes, tools, groups and individuals. The bottom line is that companies need to find ways to innovate without having to disrupt the very competencies that have made them and continue to make them successful.

To this end, Adaptive Innovation sees new companies emerging that will manage these complex activities on various levels. Companies such as Nine Sigma, Yet2.com and Innocentive reflect the more transactional seeking of specific features that are already or are very close to commercial application. On the other hand, traditional design and branding companies, such as Ideo, very capably serve the development of customer experiences utilizing generally known commercial technologies.

We also see another class of firm emerging, whose job it will be to facilitate the development of breakthrough technologies where a complex combination of innovations and inventions are required to transform an industry. These types of breakthroughs are difficult to achieve alone and often require an approach that for most firms is so different from their current activities as to be distracting and thus difficult to effectively implement. Accordingly, we see a strong need to be able to pull together a vast array of expertise, information, resources and capabilities on a constantly changing basis. Especially important to speed, efficiency and effectiveness will be the requirement that one have access to the best minds and capabilities on a just in time basis. Most firms cannot afford to have such expertise on staff on the chance that they might need them one day or even one hour a year.

A company that can facilitate not only the management of these resources, but access to them as well as the management of the insight, innovation and invention processes for complex breakthroughs will be a key to innovating in the 21 century. The key we see to Adaptive Innovation will be the management of all of these activities on a global basis and we are striving to be one of the first to effectively implement it. We even see a new scientific discipline emerging to train practitioners called by its originators at Georgia Tech “Strategic Engineering”. Strategic Engineering’s focus is the management of a the wide range of disciplines required to develop the complex solution mandated by today’s innovation ideas, from engineering to design to economics to business management. In fact, our most recent successful start-up, Sirrus (formerly Bioformix) was completely developed on the principles of Adaptive innovation.

When we created Sirrus, Steve and I had noticed some verity simple trends that were being exploited in on their face seemingly strange ways. By example, to solve our energy conundrum, billions were being invested in new sources of energy, sustainable sources of energy and then chemicals that seemed bizarrely inefficient. Historically, no totally new energy form or chemistry simple merged and was adopted within literally a decade or two on a global, billion-person scale. Why them did anyone at all expect that doing so now was going to mystically different, easier and more likely?

Instead, we simply asked the question – what must be true to eliminate this conundrum in all of its facets, not simply the energy itself? How about turning the switch off and not using the power at all versus finding new sources of energy? Turning off a switch just seems a whole lot simpler. Well, at Sirrus, formerly Bioformix, we had been searching for years for a way to eliminate or radically reduce energy use and when we came across efforts in zero energy, high speed curing polymers that actually had kick ass properties, we realized not only could save manufacturing energy – we could change what things were made of and how they were made and then how they were delivered to the consumer. Just-in time, highly enhanced cabinetry delivered in 24 hours to consumers, auto finishing where without heat and solvent, all parts could be finished the same way in the plant and in the suburbs and BPA elimination at lower costs than current products, not higher. How about ultra light weight cars without needing carbon fiber…. How much energy possibly? Five (5) Quadrillion BTU’s or 5% of American energy consumption alone could be saved. Sirrus is our best proof to date that Adaptive Innovation can work.

Adaptive Innovation is therefore a very effective, simplified, holistic approach to innovation where one seeks to have access in real time to a vast set of resources, capabilities, processes, tools, groups and individuals to facilitate the consistent, effective, efficient development of insights to develop innovate ideas that are ultimately translated into commercial inventions that create value. You do not need to use all of that – you simply need access top the tools you need when you need them. No pre-set, rigid process, no dozen stage gates. – just a whole lot of common sense. Yes, for more complex breakthroughs, the more critical the management of multiple, highly varied disciplines will be, but the point is that it’s not needed all the time, very time. For most innovations, consistently defining and communicating simply, clearly defined needs and memories of the futures and their why must be trues coupled with most companies already existing processes that are capable, proven will enable employing Adaptive Innovation.